kidding around

carried my mother

piggy-back

I stopped dead, and cried.

she’s so light …

wrote GREAT

in the sand

a hundred times

forgot about dying

and went on home

fling my

arms and legs

all over the room

then, calmly

get up again

Ishikawa Takuboku

kidding around

carried my mother

piggy-back

I stopped dead, and cried.

she’s so light …

wrote GREAT

in the sand

a hundred times

forgot about dying

and went on home

fling my

arms and legs

all over the room

then, calmly

get up again

Ishikawa Takuboku, writing in the early 1900’s, is best known for his poems written in the tanka form. Much like haiku, but with a bit more room to detail a particular moment, tanka capture the essence and impact of an emotional (and often physical …so, somatic) event. Tanka also allowed for the “overwhelming personalism” Takuboku brought to his work (Sesar, C., Takuboku: Poems to Eat, 1966).

After experimenting with Japanese “new-style” poetry that aimed to integrate traditional Japanese forms with European free-verse, Takuboku ultimately decided that tanka was the ideal form for conveying a single emotional event. In the article Poems To Eat, he states, “people claim the tanka is too short to work with, but I think that is precisely the advantage. Isn’t it so? A small poem, that doesn’t take time, is best — it’s practical.” Takuboku rejected pretentious notions such as “poets,” and asserted that the only condition for being a poet was being human. “Somewhere along the line [he] was jolted out of [his] childish infatuation” with high-powered notions and poems that “were nothing more than a surrender to hackneyed sentiments,” (Takuboku: Poems to Eat, C. Sesar, translator, 1966.)

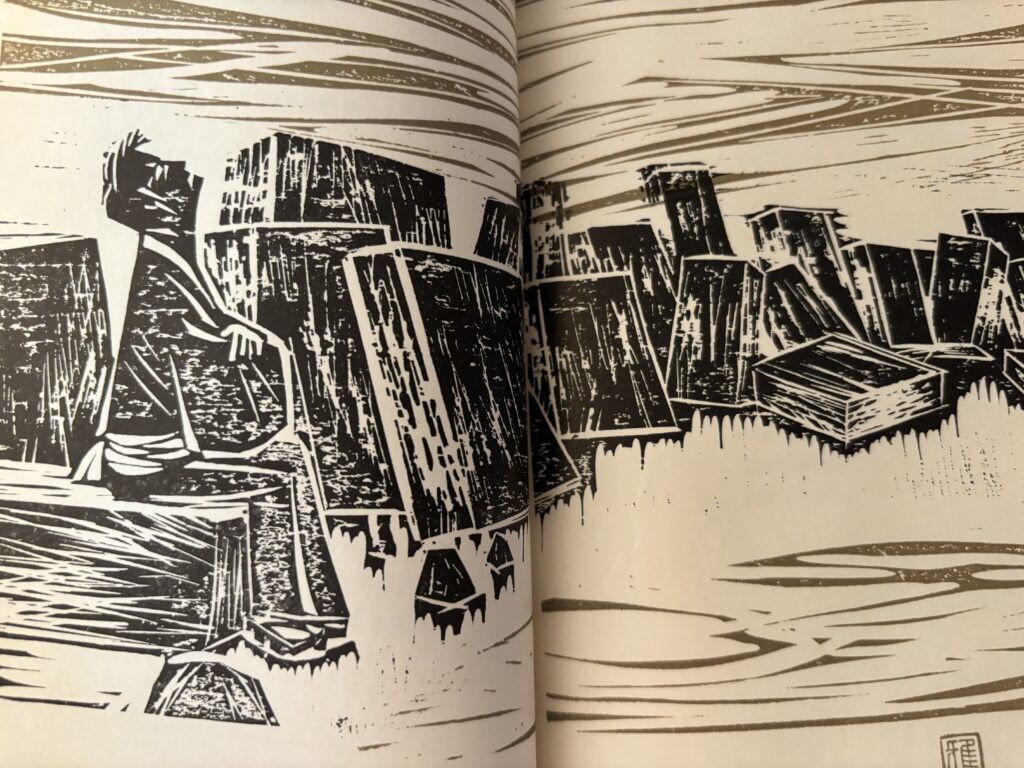

My friend, Jeffry Beuchler, gifted me with a gorgeous copy of Takuboku: Poems To Eat while I was studying dance/movement therapy and somatic counseling psychology at Naropa University. I found his poems delightfully refreshing, especially as respite from the rigor and slog of academic writing. They were like gestures — not unlike the very specific gestures arising in authentic movement or in modern dance choreography.

For me, they seemed to capture nuances of human experience that die in translation when we try to over-language or language over them. Takuboku’s poems were also courageous: they jumped straight into the messiness, darkness, sadness, and foolery of what is it is to be human with a kind of honesty that made me feel alive and kind of giddy. Something about these unadorned plunges can have the effect of waking us up to our own condition — like a witness with some perspective — and, thus, provide a doorway to laughter, if not connection and compassion. Like a Zen priest slapping the floor, these poems are great antidotes to the quick sands of neuroticism and self-obsession.